Chapter 57

The river is an immaterialspecies of magnetic power in the sun. So why not have the oar to borrow something from the magnet? What if all the bodies of the planets are enormous round magnets? Of the earth (one of the planets, for Copernicus), there is no doubt. William Gilbert has proved it. -- (p.550)

Physical Causes

Kepler's method of reciprocation in chapter 56 has given him the correct distances, but he could not conceivably present this reciprocation theory as the true motion of the planets without a reason for why they would reciprocate in precisely this way, along the diametral distances, as opposed to reciprocating in some other conceivable fashion.

Kepler poses the need to look for a natural cause of the planet’s reciprocation, first giving the example of a sailor with an oar. As the planet is moved through the circular river of its orbit, the sailor rotates his oar at a rate of one rotation for every two planetary orbits. In this way, the oar is always placed in such a way as to drive the planet towards the sun in the descending semicircle, and force it away in the ascending. (This is similar to chapter 38.) Imagine a circular river flowing through the orbit.

Yet,

While the force of a river is material… the force of the sun is immaterial. Therefore, the comparison with the planets ought to be different: they need no oar, no physical instrument, for catching hold of the force of some weighty thing (for that motive species of the sun has no weight). Nor do we deem it fitting that the stars have corporeal oars, seeing that we hold them to be round.

But from this very refutation, there comes another example, which will perhaps be more suitable. The river and the oar are of the same quality. The river is an immaterial species of magnetic power in the sun. So why not have the oar too borrow something from the magnet? What if all the bodies of the planets are enormous round magnets? Of the earth (one of the planets, for Copernicus) there is no doubt. William Gilbert has proved it.

Natural Principles: The Magnet

Kepler introduces magnetism as the mechanism by which the planet approaches to and recedes from the sun."But to describe this power more plainly, the planet's globe has two poles, of which one seeks out the sun, and the other flees the sun. So let us imagine an axis of this sort, using a magnetic strip, and let its point seek the sun. But despite its sun-seeking magnetic nature, let it remain ever parallel to itself in the translational motion of the globe, except... the progressive motion of the aphelion."

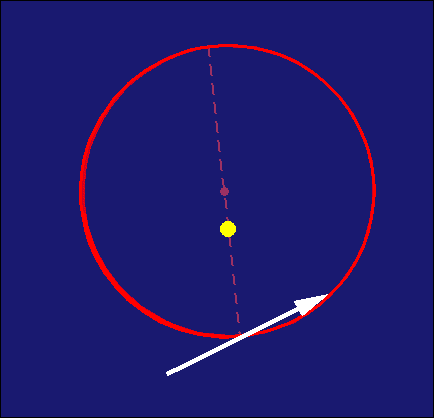

On the left side of the planet's orbit, the attracting side of the magnet is facing the sun, and the planet's distance from the sun decreases, while on the right side, the repelling side of the magnet faces the sun, and the planet's distance increases again. Note that for Kepler's idea, the sun is a magnetic monopole -- it always attracts the same side of the planet's magnet, no matter the orientation. Here you have the planet's motion, with a line from the sun to the planet drawn in to help you see the changing distance:

This magnetic motion even gives a reason for the slow motion of the aphelion:

For suppose that this force of directing the axis towards the sun does detract somewhat from the retentive power [of keeping the magnet parallel to itself]... Accordingly, in the aphelial semicircle the point will gradually incline backward... Thus the aphelion will become retrograde... But in the perihelial semicircle... will then be made to move forward, and to be fast... [T]he force tending to turn the magnetic axis towards the sun is therefore stronger at perihelion than at aphelion... And so the reason is clear why the apsides progress, and do not retrogress.

The attracting side of the magnet is pulled towards the sun, while the repelling side is pushed away. Thus, at aphelion and perihelion, the magnet will be given an impulse to rotate. But this impulse is stronger at perihelion (represented by a larger arrow) than at aphelion, and thus, the net result is a progression of the aphelion in the same direction as the motion of the planet (it progresses, rather than retrogessing in the opposite direction).

Click for animation.

Now, this magnetic action corresponds to the general motion of the planet (approach and recession), but does the physical action of a magnet correspond to the specific diametral reciprocation put forward in chapter 56?

Magnetic Action

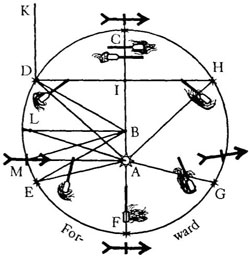

This is Kepler’s representation of the action of the magnet. This is an image of the body of the planet, with the direction of the magnetic fibers indicated by the arrow, as in the above animations. This makes the angle KBI the equated anomaly. Kepler believes that the length CN, the sine of the equated anomaly, is a measure for the intensity of the magnetic power at that location.

He begins by bringing up a conclusion he has brought up in his Optics (pp. 31-33 of the Donahue translation): that in a balance supported from the center, the angle at which the two pans rest indicates the weight in the two pans. Specifically, Kepler uses this analogy: suppose the magnet supported at B from vertical pole CB (rotate your head slightly, it helps). By his law of the balance, the mass of the pan at D is to the mass in the pan A as PA is to DP. These masses in the case of the balance are taken to be the powers of attraction and repulsion for our magnet. Since the attracting side D is closer to the sun than the repulsive side A, the attracting force minus the repulsive one will give the net attraction. Creating a point S with SA equal to DP, Kepler removes repulsive force SA (=DP) from attractive force AP, leaving him with net attraction SP. Note that this is twice CN, the sine of the equated anomaly. Therefore, the sine of the equated anomaly measures the intensity of the magnetic power.

But what is the result of the constant application of this magnetic approach and recession? The diametral reciprocation of chapter 56 demands that the versed sine of the eccentric anomaly be the measure of reciprocation:

Instead of taking the distance from the sun to the eccentric location, the hypothesis of chapter 56 requires that the “diametral” distance be taken instead, from the eccentric position on the circle to the perpendicular from the sun to the diametral line. This is shorter than the distance at aphelion by the amount shown in red − the versed sine of the eccentric anomaly. That is to say, the planet is at a distance to the sun that is closer than the aphelial distance. The amount closer is measured by the versed sine.

Try drawing other angles on paper. How large is the versed sine at 0° eccentric anomaly? How about 180°?

Reconciliation

Kepler sets out to determine whether the sum of the impulses supplied by the magnet (which are each measured by the sine of the equated anomaly, CN, in blue) come out to be the same as the versed sine of the eccentric anomaly, HI, in red. Note that the line BG (not drawn), if extended, would reach the center of the orbit, making GI the eccentric anomaly, and HI its versed sine -- the measure of the reciprocation from chapter 56. To look at the ongoing effect of the magnetic power, Kepler sets out to add the sines for the first 90 degrees of the circle, to compare to the versed sines as he goes. Rather than adding CN, however, he uses GH, the sine of the eccentric anomaly, since the two are very close. He finds that there is an incredible match, although the sum of sines is slightly larger than the versed sines. (Click here for an Excel spreadsheet of the sums of the sines compared to the versed sines.)

Is Kepler performing an integral here? Can you think of a way of demonstrating that the sum of the sines is exactly the versed sine?

But this error confirms his hypothesis − since the sines of the equated anomaly (CN) are always slightly smaller than the sines of the eccentric anomaly (GH), Kepler reasons that this error will correct itself: the sum of the smaller sines should give precisely the versed sine of the eccentric anomaly.

With this astounding demonstration, Kepler’s diametral distances are no longer geometric conveniences; they are physical necessities, in accord with the action of the magnet.

But how can the magnetic mechanism be maintained? It seems impossible for our Earth, since the orientation of our axis does not place us at the equinoxes when we are at the apsides, as this magnetic faculty would have to do, were it aligned with the earth’s axis. Although Kepler does not point this out here, the fact that the equinoxes precess while the aphelion progresses indicates that the magnetic power cannot reside along the direction of the axis. No part of the earth remains pointing the same direction except its axis, and it points the wrong way.

Although the magnetic hypothesis creates the correct distances, there is no physical way to keep the magnet pointing in the correct direction -- a failure of the hypothesis.

A Planetary Mind?

With this failure, Kepler proposes a planetary mind. This mind could use the changing apparent size of the sun as its guide for motion. Kepler proves that when the diametral distances of chapter 56 are used, the increase in the apparent size of the sun (measured as apparent angular size) is measured by the versed sine of the equated anomaly.

Here, ν is the eccentric position of the planet at 90° of equated anomaly, before the reciprocation of chapter 56 is performed. This reciprocation puts the planetary distance at ο. Kepler proves that οζ is to ογ as ζξ is to γζ, which means, from a proof by Euclid, that angle ζξγ is bisected by ξο.

But if ζξο and οξγ are equal, then angle αοξ, the apparent size of the sun at 90° equated anomaly, is as much larger than αζξ as it is smaller than αγξ. Therefore, the apparent size of the sun has achieved half its increase at the same time as the versed sine of the equated anomly has achieved half of its increase (0 at γ, 100,000 at ο, and 200,000 at ζ).

After further working through the requirements of this mind, Kepler is not fully satisfied, and leaves open the question of the natural (magnetic) cause, or the action of a mind, pointing out that the natural cause gives a “splendid occasion for the motion of the aphelia.” Whichever is chosen, either one provides for a reciprocation based on the diametral construction of chapter 56.

A Physical Orbit

For both the magnet or the mind, the center of the orbit is no longer needed. For the magnet, the constantly acting power of the magnet, proportional to the sine of the equated anomaly, produces an effect equivalent to the versed sine of the eccentric anomaly, but the eccentric anomaly is now only a measuring point. It is not required to exist − the reciprocation of chapter 56 is made only by considering a force determined by the equated anomaly. For the hypothesis of a mind, the sine of the equated anomaly can be known physically by the planet, and the versed sine of the equated anomaly is used as the index of the required size of the body of the sun.

Thus the eccentric anomaly, and the center itself, are no longer needed! What does the “eccentric anomaly” even mean now, and what is a center? Without a circular orbit, the requirement of a point from which the planet maintains a constant distance disappears. Kepler:

Furthermore, when one removes the cause for keeping watch on the center, the effect is also removed. But the center needs to be watched if the circle is to be traversed. However, the planets’ orbits are not perfectly circular, as was proven from the observations… Therefore, the planets do not take aim at the center. And thus this putative center is actually secondary to the path. But if it were watched by the planet, it would have to be prior to the path.

Now, the center does not exist on its own as a geometric location, but is physically determined as the result of the physical causes governing the motion of the planet.

Moving on…

Now that Kepler has a physical justification for the diametral distances of chapter 56, he will take up the error in the equations that he finds in implementing this hypothesis.

| Chapter 58 |  |